Main navigation

Chair's Welcome Message

Greetings on behalf of the Department of Sociology & Criminology faculty, staff, and students! I hope that you and your loved ones have remained well this past year. While we’ve waited a long time for spring to finally arrive, we have had many exciting developments this year.

First, the Board of Regents has approved our new PhD in Criminology that will launch in Fall 2023. Our program will be the first and only PhD in Criminology program in the state of Iowa. The addition of this program within our department will fill an important niche in graduate training in criminology nationally by drawing on the strengths and availability of graduate coursework and faculty expertise within sociology, particularly in the study of social stratification, mental health, and social psychology. Students in both the Sociology and Criminology PhD programs will benefit from our rigorous methodological training and the opportunity to take substantive courses in both disciplines as well other opportunities for interdisciplinary work offered in other departments at the University of Iowa. Additionally, in preparation for the new PhD program, we were able to hire an additional faculty member. We are delighted to announce that Amber Powell will be joining our faculty in the fall, after completing her dissertation at the University of Minnesota.

Another wonderful development this year was a generous gift from Anna Mary Mueller and her daughters Elizabeth Larson and Rachel Mueller, which has enabled us to establish The Charles W. Mueller Fellowship Fund. This fellowship will provide summer research support for graduate students and further continue Chuck Mueller’s lasting impact on our graduate program. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Anna Mary, Elizabeth, and Rachel and each of you who have given generously to the department. These gifts allow us to enhance our teaching and research missions in valuable ways, including sponsoring the activities of our sociology and criminology undergraduate honor societies and helping us bring visiting scholars to campus to share their work and meet with our students. We greatly appreciate all continued and new support! This year’s speaker for the Robert and Clarissa Rees Lecture Series was Dr. Celeste Campos-Castillo. This annual presentation by an undergraduate or graduate student alumnus is funded through the generous support of alumna Marian Rees. Professor Campos-Castillo received her PhD in 2012 and is Associate Professor at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee and soon to be Michigan State University, and she was the recipient of the 2022 Midwestern Sociological Society’s Early Career Scholarship Award. During her visit with us she presented her fascinating research on the implications of gossip on social media platforms for adolescent wellbeing.

I would like to take a moment congratulate our graduating students who have persevered through an incredibly challenging time. You can read about many of their future plans and accomplishments here. Congratulations also go to our 2022 winners for the Outstanding Senior Awards, Brianna Perez and Regan Smock. Brianna is a Criminology, Law, and Justice major and is also graduating with minors in Philosophy, Social Justice, and Rhetoric and Persuasion. She has been an active member of many campus and department organizations, including Alpha Phi Sigma (The National Criminal Justice Honor Society), the University’s Association of Latinos Moving Ahead, the Campus Activities Board, and president of the Mock Trial team. She also served the Associated Residence Halls as Vice President of Catlett Hall Association and Marketing Director of Petersen Hall Association. Recently, she interned at the Will County Public Defender’s Office. After graduation, Brianna will follow her passion and pursue a J.D. Degree from the University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law. Regan Smock will receive a Bachelor of Science degree in Sociology with a minor in Spanish. She has served as the President of the Undergraduate Student Government, Research Ambassador for the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates, Director of Academic Affairs for the University of Iowa Student Government, Orientation Leader for Orientation Services as well as Peer Mentor for the UI Tippie College of Business. Regan was selected as an Undergraduate Research Fellow by the Iowa Center for Research by Undergraduates. You can read about her honors thesis research in our newsletter. We are lucky to have had Brianna, Regan, and all of our recent graduates as our students, and on behalf of the department I want to wish them the best of luck in the future!

Our faculty and graduate students have continued to excel in their research, teaching, and public engagement endeavors. To name just a few accomplishments, Professor Freda Lynn was the recipient of the Hubbard-Walder Award for Excellence in Teaching, graduate student Liz Felix received the Office of the Vice President of Research Graduate Research Excellence Award, and Professor Louise Seamster was a guest on the Ezra Klein Show podcast to discuss her research on the student debt crisis. Please check out our Facebook page and the news section of our webpage to keep up on all the happenings in the department.

As you move forward through 2022, please feel free to drop us a line—we are always happy to hear from you.

Warmest regards,

Jennifer Glanville, Professor and Chair

The Journey of 2003 Alum, Jenny Qin

We chatted with 2003 graduate, Jenny Qin, about her experiences in our department, the impact of her Sociology degree on her career, and her advice for current students. Jenny graduated from the department with an MA in Sociology. Her thesis project was on the effects of cohabitation – unmarried couples living together. She is a Global Vice President at Loparex LLC and recently visited their plant in Iowa City.

Please enjoy the interview (lightly edited for clarity and space).

SH: What are your best memories of Iowa?

JQ: One of my favorite classes was “Graduate Proseminar,” because it was a new way of learning for me. In China, we listened to lectures. At Iowa, we got to speak up and discuss our viewpoints. I still remember my American classmates confidently speaking up and sharing their opinions while I was worried that people would laugh at me. I soon became more comfortable speaking up. It was good practice as I now can think on my feet, form a perspective, and articulate it clearly, concisely, and logically. I remember doing homework with Minglu Wang and Chang Liu at the “computer room” in the basement of Seashore Hall. We were all international students. I was 19 and they were like my big sisters. They made it easier to study and live in a new country. I assisted with social psychology research at the Center for the Study of Group Processes. It is interesting to study people, observe their behavior, analyze it, and draw conclusions. In turn, learning from the findings helps me better relate to people.

SH: Tell us a bit about your career and how your sociology major informs what you do now.

JQ: I am currently the Global Vice President at Loparex, responsible for running the global Tapes and Electronics business for the company based in Cary, North Carolina. After graduating with my master’s degree in sociology, I earned a Master of Accountancy from Tippie College at the University of Iowa. I worked for a few years and then earned an MBA from the Darden School at the University of Virginia. Then at W.R. Grace and Company, I worked my way up for seven years before joining Loparex in 2018. Sociology, especially social psychology, informs what I do now not only at work but also in my personal life. My first exposure to social psychology was through Professor Michael Lovaglia’s book, Knowing People: The Personal Use of Social Psychology. As he said in the book, social psychology is about knowing people, ourselves, and others. Social psychology permeates our lives every day. It could be writing in my journal about how I could have handled a situation differently. It could be about reading between the lines of what people say. It could be about choosing words carefully to send the message I intend to send. Social psychology is lifelong learning for me in this field.

SH: Lastly, what advice do you have for future graduates from the Department of Sociology?

JQ: My advice is to be fully engaged in your sociology program, whether or not you plan to pursue a career in sociology. Put in your best effort and make excellence a habit. You will be well prepared for success.

Mark Berg’s World-Class Research Rooted in Iowa

By Michael Lovaglia

Professor Mark Berg’s research brings together ideas and techniques from two very different areas in sociology – criminology and the social aspects of health. The impact of his publications and the breadth of his research have earned him the title of Collegiate Scholar, awarded by the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Iowa. His article on the spread of the opioid crisis through the heartland of America, “The Opioid Hydra,” won the Fred Buttel Outstanding Scholarly Achievement Award from the Rural Sociological Society in 2021.

Michael Lovaglia interviewed Mark Berg for the Newsletter (condensed and lightly edited for clarity).

ML: Our readers would be interested in your Midwestern roots and how you came to be a professor at the University of Iowa.

MB: I stumbled into the social sciences. Growing up, I was encouraged to pursue a career in veterinary medicine. My father was a farmer and being a vet was a respectable career that he was familiar with from working with his swine herd. The hope was that my curiosity about the social side of life would eventually dwindle.

One event that shaped me was the farm crisis of the mid-1980s. I was 9 or 10 years old. It lasted about a decade and drastically changed small farming communities. Businesses were closing. People were leaving the farm and working in town. People in that culture had skills passed down for generations that only prepared them to work in agriculture. They became in some ways irrelevant to the changing society. Prominent musicians held benefits to raise money for people struggling in farming and small-town communities. I remember in churches, people would post crosses, each one symbolizing a farm that had been foreclosed and taken over by banks. That’s when I began to think about how social context shapes health and well-being and behavior, which eventually became a big part of my research.

I grew up in a community where most of my friends worked in the farming economy or in manufacturing. Few had white-collar jobs. Some were secretaries or worked for the church. I grew up in the Catholic church and went to Catholic schools. It was imposed on me. It also made me feel that I lived in a community that both collectively socialized its children and monitored its children. I was careful not to break the rules because I didn’t want to suffer the shame of people who played bridge with my grandma, who went to high school with my mom. That was a more powerful motivator than any worry about getting caught and juvenile sentencing.

Looking back, we tend to color things in favorable ways if we have had favorable outcomes. Some people I knew went to prison, but we all agree that it was a community that collectively banded together. People knew each other with ties going back generations.

I grew up about 70 miles from the Nebraska border north of I-80. Iowa City is a wonderful place but so different from small communities in western Iowa. In some ways, I will always be an outsider – especially in academia! Sociologists are observers and that distance helps. Talking with my brothers, for example, their working day is defined by pain, by how tired they are. They are the kind of people who go to work the next day with their arm in a sling after breaking it in a farming accident.

ML: You also study crime.

MB: I still don’t know how I ended up in criminology. It is interesting how, despite all the hardship that people went through, they still maintained a healthy lifestyle and worked to help other people. Criminology wrestles with inhibition. Why don’t more people commit crime might be a better question than, why do so many people commit crime? I’m fascinated with restraint and inhibition. Not why people engage in harmful acts but why they don’t.

We are selfish but we rarely do things that actively harm other people. A Viet Nam vet wrote that he learned we didn’t have to teach young men how to do atrocious things to people, the tendency was already in them. That energized my interest in restraint and change. When people have committed serious crimes, some adopted a new identity and started a new positive life. Others embraced their past and said, “these are the bad things I did, let me warn you how not to do it.” Most young men have fantasized about killing someone but very few act on that impulse. That’s enormous social control.

As a criminologist, I lean more toward social psychology. Recently I’ve drifted more into research on health outcomes. It shares some of the same concerns as criminology. Social integration affects both health and the likelihood of committing crime.

With a team from the University of Georgia, I’m working on early childhood trauma, such as child abuse and neglect, and how it impacts adult health. If you survey older people about current health and childhood trauma, those early events seem to have profound effects on later adult health. But recent research casts doubt. When you ask children, they will tell you one thing about the events in their life. But those don’t seem to affect their health later. It’s the memory of childhood trauma, not the event that seems to matter for adult health. Why would the memory of trauma matter but not actual traumatic events in childhood?

To solve the mystery, the team followed kids from age 10 through their 30s. As expected, the bad things kids reported at age 10 don’t match well with what they remembered at age 30. Memories change over time. Bad early events reported at age 10, however, did strongly predict a biomarker for heart disease risk at age 30. Childhood adversity does matter for adult health. And the memory of early life adversities matters as much for self-rated health as it does for physical indicators of health in adults. Childhood adversity matters for how healthy adults think they are, as well as for how healthy they actually are.

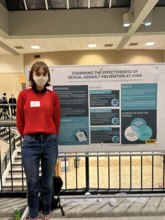

Regan Smock: Undergrad Research with Important Impact

By Bodi Vasi

Students in our undergraduate programs have opportunities to learn research design and statistical techniques, and some of our best students use these tools in independent research projects. Regan Smock is a senior studying Sociology and Spanish, who came to us from Coggon, IA. Regan conducted research to assess the effectiveness of sexual assault prevention at the University of Iowa using data collected from a survey given to University of Iowa students in 2015. The survey asked about the kinds of sexual assault prevention training that students had taken, both before enrolling at the University of Iowa and since they arrived. It specifically asked whether students had taken the Bystander Intervention training offered here at the UI. The survey also asked about effective behaviors that students might have practiced to prevent sexual assault. For example, one question asked students whether they had ever walked a friend who had too much to drink home. By comparing student reports of effective prevention behavior with the sexual assault training they had taken, Regan tried to see how effective their training had been.

Regan used a statistical technique called linear regression to assess which trainings had a significant impact on students’ reported bystander intervention behaviors, like walking a friend home after a night out. The analysis showed that students who completed the Bystander Intervention program at the University of Iowa were more likely to intervene to help others after witnessing a person in trouble than were students who had not completed the training. That difference was statistically significant, which means that it is likely a real result rather than a random difference between individuals. Because of Regan Smock’s research, we now have scientific evidence that the Bystander Intervention training works.

Outside of the classroom, Regan is involved with Undergraduate Student Government and works in the Department of Sociology and Criminology as a Research Assistant. Regan enjoys hiking, crocheting, and spending time with her cat, Mochi. She plans to pursue a Ph.D. in sociology after graduation.

New Fellowship Fund to Support Students in Honor of Professor Charles Mueller

Anna Mary Mueller, along with her daughters Elizabeth Larson and Rachel Mueller, has established a fellowship fund in honor of her late husband and former faculty member, Charles Mueller. Chuck was a professor of sociology at Iowa for 32 years. He was beloved by his students and a renowned scholar. His research made major contributions in several areas, especially in the sociology of work and organizations. He passed away in 2013.

The Charles W. Mueller Fellowship Fund will provide one or more summer fellowships to graduate students starting in 2023. Summer funding means a lot to graduate students because most fellowships offer support only for spring and fall semesters, leaving them to scramble for funds during the summer months. By extending student support, the new fund will honor Chuck’s memory and enhance his legacy of helping students whenever he could in his role as Director of Graduate Studies for sociology.

The Department of Sociology and Criminology is fundraising to match his family’s donation. If you would like to donate, please visit this link.

The Pandemic Life of Kelci Mueller

By Bodi Vasi

A conversation between Bodi Vasi and Kelci Mueller about life during the pandemic (lightly edited for clarity and space).

BV: How has the pandemic influenced your studies?

KM: I was part of the cohort of graduate students that came to the U of Iowa when the pandemic started. COVID not only impacted our transition into graduate school, but we also had to transition online. Everything was email and Zoom. It was difficult to stay engaged since we no longer had in-person connections. The transition also delayed my timeline but then it got better. We figured out how to work from home and navigate the online space as a learning tool. Before I would have thought that a meeting had to be in person, but arranging online meetings is easier.

BV: Has the pandemic changed your relationships with other students or with the professors?

KM: Yes and no. On the negative side, it made it harder for us to really get to know graduate students who were not in our small cohort. It also was difficult to network with professors outside of classes because we were not passing them in the hallway. Even in online meetings, there is not much room for one-on-one conversations, which are coming back now, thankfully.

BV: Was there anything positive about life during the pandemic?

KM: The flexibility of getting together online is good. I also do not get sick with minor illnesses as often because of the masks. The pandemic shed light on how important close relationships are, especially when things are feeling uncertain or scary (and potentially losing loved ones due to the pandemic). We luckily had social media, texting, phones, and Zoom to keep connected with those relationships. It showed how important those forms of communication are in modern society. I cannot imagine what life was like in the early 1900s!

BV: What sociological insight can you apply to make sense of the pandemic?

KM: Close friends and family as well as social networks are important to our mental health and wellbeing. It took time to adjust to the fact that we could not physically see some people in person. That made it even more important to stay connected to those that we love and care about. I am normally very shy and do not do well in large crowds or classrooms, but just being around other people helps. The human connection comes from that. During the pandemic, we did not have that normalcy, and online contact with our primary social groups helped with mental health.

BV: What lessons have you learned about human nature or “the meaning of life”?

KM: That we all need each other to survive and function. America especially has this idea of everyone for themselves and rugged individualism. The pandemic made clear how much we rely on other people to keep us healthy, both in terms of not spreading the virus but also for mental health. It also made me more empathetic towards others and emphasized that every life matters regardless of where they come from, who they are, and especially what they believe.

Symposium on Corruption, the Rise of Populism, and the Future of Democracy

By Michael Lovaglia

Professor Marina Zaloznaya has been in the media spotlight due to her important and timely research on corruption in Russia. Her research shows how everyday corruption, such as payoffs to building inspectors or other public officials, hampers the progress of societies struggling toward democracy. Ukraine and Russia are currently the most prominent examples because of the conflict between them. To advance our understanding of the problem posed by corruption, Professor Zaloznaya, and her colleague from the Department of Political Science, Professor Bill Reisinger, organized a three-day symposium bringing together many of the top researchers in the field. Professors Jennifer Glanville and Michael Sauder from our department helped too. The symposium titled, “Corruption, the Rise of Populism, and the Future of Democracy,” was sponsored by International Programs at the University of Iowa.

In the symposium’s first session, Professor Zaloznaya and her co-author Professor Bill Reisinger presented conclusions related to their large-scale survey research in Russia in a talk titled, “Governing through Corruption: The Case of Public Sector Bribery in Russia.” Related talks in the second session built to a surprising conclusion. Professor Marco Garrido from the University of Chicago presented his work on “Populism as Anti-Corruption Movements” and Professor Michael Levien from Johns Hopkins presented his work on “Redistribution and Exclusion: Value Articulations and the Populist Movement.”

According to Professor Zaloznaya, research on corruption leads to the conclusion that recent anti-corruption efforts in many countries helped anti-democratic populist politicians rise to power on the promise of reducing corruption. Then, once in office, not only did these populist politicians weaken democratic safeguards, but they also increased corruption as a governing tool. The pattern of weakening democracy while increasing corruption also can be seen in well-established democracies such as the United States.